All done! The exhibition was a success although the amount of last minute running around I had to do was a bit of a worry. All the feedback I heard was positive which is great! and it looked good too. Once the report is out of the way today its all over and done with for good. Overall it was a good experience though, and I really did learn a lot so I am grateful for that.

Thursday, 15 November 2018

Thursday, 8 November 2018

Professional Practices 31/10

Exhibition space looks great.. now that we finally have the key. I had to chase down someone completely different to get it in the end. We spent a good hour or so in the room just talking plans out and working out possible complications. Jessi is going to talk to her dad about some big S hooks to potentially hang up the pallets in the space. I managed to get most of the info sheets back, including the ones i had to reprint and make some ppl do right there and then in class. I am excited, but also a little concerned that we arent ready at this point for anything, it wouldnt take much to derail this exhibition right now.

Photography 8/11

Todays class we managed to successfully get everyones finished pieces hung in the arcade ready for tomorrow. Im really glad I was finished last week because I definitely would not have had time to do anything on my own today. The exhibition space looks great and everyone's pieces are quite cohesive for the most part. My last minute hanging solution of the eye hooks seems to be working, and will make it easier for me to hang once I get the pieces home.

Photography 1/11

Yay! all printed this week. I really like the look on the matte paper except the ink is a bit powdery on my fingers. I did manage to get my work onto the foam core eventually thanks to Leigh and Alex sticking around after class for me. It would have been easier if I wasnt helping the others while they cut their foamcore but not everyone is as quick as me with the box cutters. Good thing I am patient lol. Its a nice feeling to have it ready the week before its due. Definitely the only project this time around that I had ready early.

Photography 25/10

After playing around, I managed to split the pinhole image nicely into thirds so that is going to be my final image. This week is all about playing with tone and matching up the parts of the lino cut with each section of my triptych. I quite like the contrast between the sharp print images and the soft photo.

Tuesday, 6 November 2018

Film/Sculpture 2018 Visual Diary digital copy

Due to my final piece being a video/audio piece, I have decided to copy over my diary into this blog so I can add some audio samples and video tests to my research.

Nostalgia - https://www.dictionary.com/browse/nostalgia

A wistful desire to return in thought or in fact to a former time in one's life, to one's home or homeland, or to one's family and friends; a sentimental yearning for the happiness of a former place or time.

Music-Evoked Nostalgia

https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/mental-mishaps/201105/music-evoked-nostalgia

Why do certain songs send us back?

Posted May 06, 2011

I found myself falling through my memories backwards in time after hearing a song from my high school days. A single song made me feel like I was 18 again while reminding me that I'm substantially older. For me, music can induce nostalgia quickly and easily.

Other sensory experiences can induce nostalgia as well. Proust, in the most famous literary example, was sent falling into nostalgia by the taste of a cookie dipped in tea (a petite madeleine, if you are looking to try the famous memory cookie). For others, it may be a smell or a sight that evokes a long-forgotten memory.

But music seems to be a powerful memory cue for many people. Schulkind, Hennis, and Rubin (1999) documented the power of songs to bring to mind previous events and times. They played popular songs from a variety of eras for both college students and older adults. They found that songs frequently evoked memories. Sometimes, as in my case, a song would evoke a general recollection - a memory for a life period such as high school, or college, or dating that certain someone from long ago. Other times, songs brought to mind specific recollections of particular events.

Schulkind and his colleagues found that the more emotion a song generated for someone, the more likely the song would cue a memory. In addition, older songs more often evoked memories for the older participants whereas recent tunes brought memories to mind more often for the college students.

What I found really interesting is that songs often evoked memories that were general rather than specific - the feeling of high school rather than a specific event; your time with someone rather than a single date. In a word, the songs evoked nostalgia. Of course not every song brought memories to mind. Actually only a minority of songs (but a large minority) evoked memories in Schulkind, Hennis, and Rubin's study. More recently Janata, Tomic, and Rakowski (2007) also reported that songs frequently evoked memories and they reported that one of the most common emotional responses named, even by college students, was nostalgia.

So the question is why do some songs evoke memories and feelings of nostalgia while others do not?

I suspect Proust and his cookie-evoked memory may hold the key. Proust noted that he had seen madeleine cookies many times since his childhood - apparently these are a common sight in French bakeries and pastry shops. But Proust had not tasted a madeleine dipped in tea since he was a small child. To evoke memories, sensations need precise connections. Proust stated that he had not eaten the cookies, particularly not dipped in tea, since his aunt had shared madeleines with him years earlier. Thus the sensation matched the original and crucially had not been diluted by other experiences since. The taste of the tea-dipped cookie brought to mind memories of his aunt, their time together, and that entire epoch in his life. A set of events were waiting in memory, waiting for the perfect cue or reminder - a cookie.

For me, and maybe for you, a song worked the same miracle of memory. I heard a song I had not heard in years. The song evoked a sense of nostalgia for my lost adolescence. For me the song was 30 years old, but for my students an N*Sync song from the late 90s can bring feelings of middle school nostalgia (apparently some of my students have fond memories of middle school).

The risk and the joy of listening to oldies is that memories may surface. A cookie, a song, a sight, a smell, almost any sensation can lead to memories and nostalgia. The effect may prove most profound when there are few encounters with the sensation between that long ago period and the present.

The Rehabilitation of an Old Emotion: A New Science of Nostalgia

https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/mind-guest-blog/the-rehabilitation-of-an-old-emotion-a-new-science-of-nostalgia/

By Clay Routledge on July 10, 2013

A Swiss physician named Johannes Hofer coined the term nostalgia in the late 17th century to describe what he considered to be a cerebral disease unique to Swiss mercenaries fighting wars far from home. Fast forward over three hundred years to the present day and nostalgia is everywhere. Old movie franchises are resurrected and rebooted, songs and albums that represent "the classics" for any given generation are remastered and rereleased, and old video games are given a high definition facelift and resold. Communities and civic organizations all over the nation host retro-themed recreational events (e.g., classic car shows, blast from the past dances), and many social media websites thrive, in part, because people long to return to their past by catching up with old friends. These are just a few examples of the human love affair with days gone by. But why is the past so seductive? And how do we reconcile the historical view of nostalgia as an illness with the fact that this desire to mentally time travel to the past is so ubiquitous? Is the nostalgia disease now pervasive, causing all sorts of physical and mental health problems? Or was Hofer (and many scholars and practitioners since) wrong to conceptualize nostalgia as an illness? For nearly the last decade my colleagues and I have been striving to answer these and other unanswered questions about nostalgia. We were specifically interested in resolving the questions of what characterizes the experience of nostalgia, what effects (positive or negative) it has on people, and what causes people to become nostalgic. We have now conducted dozens of laboratory experiments and surveys and can, with some confidence, offer a new perspective on this old emotion. What characterizes the experience of nostalgia? Look in the dictionary and you will find a rather general definition of nostalgia as "a sentimental longing or yearning for the past" But what does it mean to be nostalgic? My colleagues and I explored this question by asking participants to write at length about an experience of nostalgia. Trained coders then analyzed these nostalgic narratives. Results from these coded narratives indicated that nostalgic memories tend to be focused on momentous or personally meaningful life events that prominently features close others (e.g., friends, family, romantic partners). Family vacations, road trips with friends, weddings, graduations, birthday parties, and holiday gatherings with loved ones are examples of the kinds of cherished experiences that people revisit when engaging in nostalgia. In addition, when coded for emotion-related words, results indicated that positive emotion-related words were used far more frequently than negative emotion-related words. Nostalgic memories are happy memories. What effect does nostalgia have on people? It is hard to imagine nostalgia as a disease when considering its content. Hofer proposed that nostalgia caused symptoms such as anxiety, insomnia, irregular heartbeat, and disordered eating. And Hofer was not alone is his view that nostalgia was an ailment that led to a number of problematic symptoms. Indeed, until the later part of the 20th century nostalgia was viewed either as a medical disease of a mental illness. However, past work on nostalgia was largely non-scientific. That is, no controlled studies were conducted to determine the effects of nostalgia. My colleagues and I thought it was time for nostalgia to be properly placed under the empirical microscope and thus began conducting laboratory experiments in which we systematically contrasted the experience of nostalgia with other modes of thought to determine its true consequences. Once we started conducting experimental studies, nostalgia started to look like an emotion redeemed. In a nutshell, we found that nostalgia does not have any negative effects on people, but does generate a number of psychological benefits. To illustrate, here is a quick rundown of a typical nostalgia experiment. Participants arrive at the laboratory and are informed that they are going to complete a survey regarding attitudes and emotions. They then complete a number of questionnaires as part of the study. Critically, some participants are randomly assigned to the nostalgia condition and some are randomly assigned to a control condition. Those in the nostalgia condition are provided with the dictionary definition of nostalgia, asked to spend a few minutes thinking about an experience of nostalgia, and instructed to briefly write about this experience. Those in the control condition are asked to think and write about a different (non-nostalgic) experience. The specific experience used in the control condition varies from study to study. In some studies, for example, control participants are asked to write about an ordinary experience from the last week. In addition, different studies have employed entirely different methods for inducing nostalgia. For example, in some studies, music has been used to heighten nostalgia. After the nostalgia or control condition, all participants complete a range of questionnaires to assess the effects of nostalgia. These questionnaires typically assess states related to psychological health and well-being. Here is what these studies have found. Nostalgia, compared to control conditions, does not increase negative emotions, but it does increase positive emotions. As I mentioned before, nostalgic experiences tend to be characterized as positive and this feature of nostalgia appears to translate into actual mood. When nostalgia is induced in the lab, it puts people in a good mood. In other words, thinking about cherished experiences from the past makes people feel good in the present. Nostalgia, compared to control conditions, increases self-esteem as well as perceptions of meaning in life. By allowing people to revisit cherished life experiences, nostalgia boosts positive self-regard and promotes the feeling that life is full of meaning and purpose. Nostalgia, compared to control conditions, increases perceptions of social connectedness. Again, as previously mentioned, nostalgic experiences tend to be highly social in nature. The consequence of this is that nostalgia makes people feel closer to others. Nostalgia reminds people that they are loved and valued by close others. These are just a few examples of the psychological benefits of nostalgia that have been unearthed in recent studies. Other recent studies further indicate that nostalgia reduces stress and makes people feel energized, inspired, and optimistic about the future. The punch line of all this work is that nostalgia is good for people. Contrary to past assertions, nostalgia does not harm people; it benefits psychological health and well-being. So what causes people to become nostalgic? Hofer thought that nostalgia was caused by continuous vibrations of animal spirits through fibers in the middle brain. Others proposed that nostalgia resulted from damage to the eardrum and brain caused by the nonstop clanging of cowbells in the Alps. Though we found these explanations rather imaginative, not surprisingly, my colleagues and I thought a fresh look at the causes of nostalgia was in order. As a starting point, we asked participants to indicate what situations or experiences tend to make them feel nostalgic. Social interactions (e.g., getting together with an old friend), sensory imputs (e.g., smells, music), and tangible objects (e.g., old photographs) commonly inspire nostalgic feelings. However, negative mood was the most commonly reported cause of nostalgia and, within this general category, loneliness was the most frequently listed discrete negative emotion. These findings suggest that nostalgia is triggered by feelings that could be described as psychological threat. But further work was needed. My colleagues and I again turned to experimental methods to further examine the causes of nostalgia. In particular, we believed that negative mood, loneliness, and feelings of meaningless would be potent triggers of nostalgia. We reasoned this because of the psychological functions that nostalgia serves. That is, as previously discussed, nostalgia increases positive mood, perceptions of meaning, and a sense of connectedness to others. Thus, people may naturally turn to nostalgia if positive mood is threatened, a sense of meaning in life is undermined, or feelings of social connectedness are compromised. Experiments we conducted supported these proposals. In one study, participants were randomly assigned to read one of three news articles that were chosen to induce positive mood, negative mood, or no emotion. All participants then completed a questionnaire that assessed how nostalgic they felt at that moment. Participants who read the negative mood inducing article reported feeling more nostalgic than participants who read either the positive or neutral mood inducing articles. In another study, some participants were assigned to a condition that made them feel lonely. Specifically, they completed a personality questionnaire and were then provided with false feedback suggesting that they were high on a validated measure of loneliness. Participants in the control condition were given feedback suggesting they were not high on loneliness. Again, all participants then completed a measure of nostalgia. Participants in the loneliness condition reported being significantly more nostalgic than participants in the control condition. In yet another study, some participants read a philosophical essay regarding the cosmic insignificance of human life (a threat to perceived meaning) while other participants read a philosophical essay that had no direct connection to perceptions of meaning. Again, nostalgia was then measured. Participants in the meaning threat condition reported feeling significantly more nostalgic than participants in the control condition. In short, situations that trigger negative emotions, feelings of loneliness, and perceptions of meaninglessness cause people to become nostalgic. The Past has a Bright Future Above, I described just a few examples of the many studies recently conducted in the field of social psychology on the content, function, and triggers of nostalgia. Though it has taken a few hundred years, thanks to a revived interest in this old emotion and a more scientific approach to studying it, nostalgia is getting a conceptual makeover. Nostalgia is not a disease or mental illness. Instead, it is a psychological resource that people employ to counter negative emotions and feelings of vulnerability. Nostalgia allows people to use experiences from the past to help cope with challenges in the present. And current research is further probing the many ways that nostalgia promotes psychological health. It appears that nostalgia has a bright future.

Some concept ideas for site installation for my piece. At this stage I have definitely decided on nostalgia as my theme but still unsure on the specifics of what I am going to do. I will admit that I am struggling this time around with sculpture purely because the film side of things has thrown me off. I do wish I had chose a simpler topic to portray.

These videos were my first attempt at capturing locations that make me think of my childhood however a frustrating breeze drowned out most of the sea noises so I didnt really get the effect I was looking for.

How Do You Exhibit Sound Art?

Margaret Carrigan

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-exhibit-sound-art

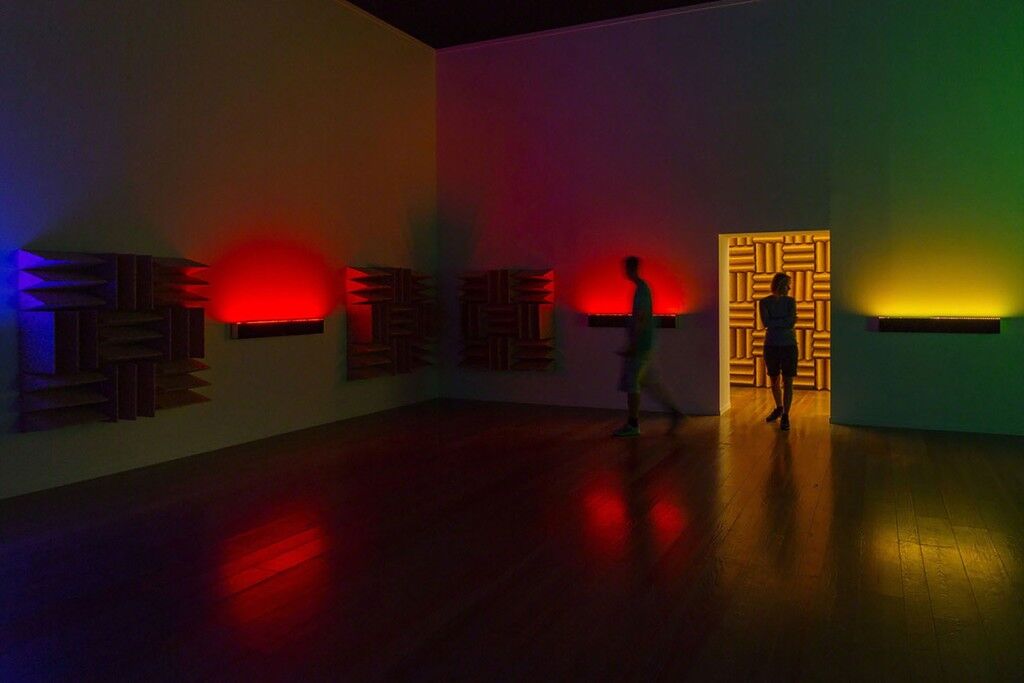

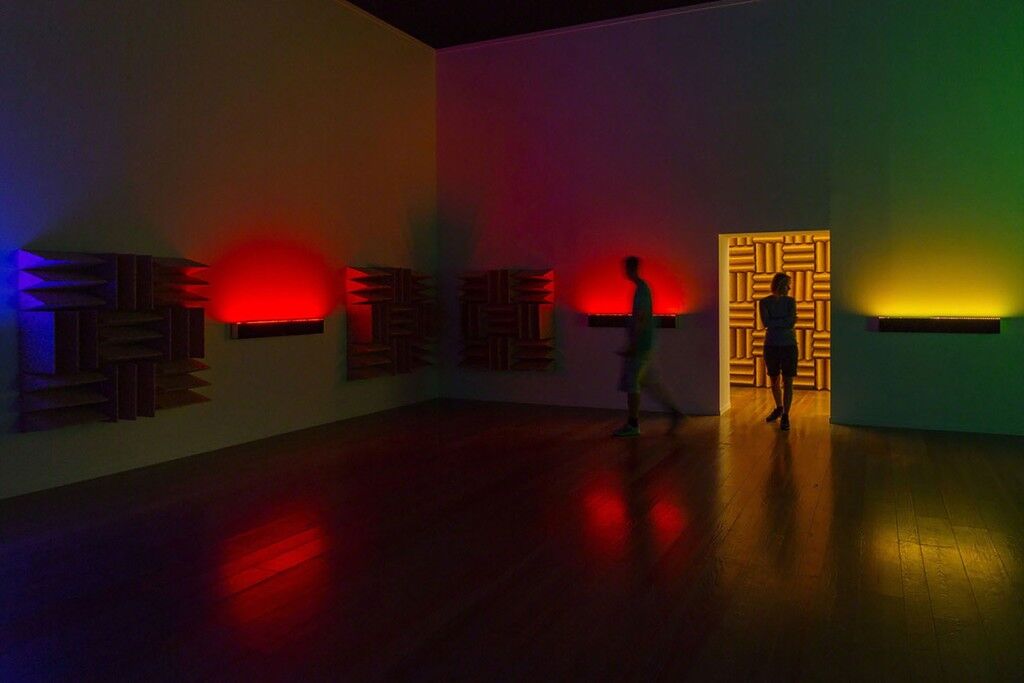

Haroon Mirza

A Chamber for Horwitz; Sonakinatography Transcriptions in Surround Sound, 2015

Lisson Gallery

Sound art

has always been a tricky proposition, for obvious reasons: Unlike a painting or a sculpture, it doesn’t stay put. This unpredictable medium has provided a wealth of potentials for artists—and challenges for curators—whether it’s being exhibited in the white cube or in the wilds of a German forest.

“The presentation of a sound piece isn’t just about the installation of whatever media player you have on hand, plus some headphones,” said Anna-Catharina Gebbers, a curator at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin. Instead, it involves what she terms “the acoustic creation of space.”

When encountering an object-based work, the viewer has much more control over the experience. You can walk up to a painting to see its finer details; every so often, you’re even allowed to touch a sculpture to appreciate its full materiality. If you don’t like what you see, you can just close your eyes—but there’s no way to naturally close your ears.

That means addressing one of sound art’s chief hurdles. Sound essentially “leaks,” according to Gebbers. “As a curator, one of the first things I think about is how can I protect the sound piece from other sounds, like those generated by audio works in its proximity, or even just ambient noise.” She explains that our brains are constantly processing audio data, prompting numerous additional considerations in order to present a sound work in a way that adequately expresses the artist’s idea while making it accessible to the visitor.

Haroon Mirza, A Chamber for Horowitz; Sonakinatography Transcriptions in Surround Sound, 2015.

According to sound artist and historian Seth Kim-Cohen, this onus falls to artists as well as curators. “When you want to picnic in the park, you have to bring your own plates, napkins, and cutlery. You don’t expect a waiter to emerge offering place settings,” he said. “Likewise, the sound artist can’t blame the curator when he’s told that he can’t play his piece on massive speakers at 110 decibels in their storefront gallery.”

In its nascency, sound art generally was aligned with developments in avant-garde music, and so work was often presented in spaces designed with acoustics in mind. Kim-Cohen points out in his book In the Blink of an Ear: Towards a Non-Cochlear Sonic Sound (2009), that sound art has always forced a re-negotiation of the established relationships between artists and their materials, traditions, and audiences, especially after World War II. In 1948, American composer and artist John Cage composed his first silent composition. The 1952 work 4’33”—which featured roughly four and a half minutes of a pianist sitting on stage in silence while the audience listened to the shuffling and throat clearing of their neighbors—became one of the foundational moments in sonic art history.

Increasingly, as sound art became woven into the practices of Conceptual and Fluxus artists of the 1960s and ’70s like Joseph Beuys, Yoko Ono, and Alison Knowles, it also functioned as a form of institutional critique, the point being to transcend the physical space of the gallery or museum. Through the 1980s and ’90s, artists like Bill Fontana and Doug Aitken were harnessing the power of new forms of electronic media to not only record and document their work, but create immersive environments or events. Those include Aitken’s multi-panel video installations and Fontana’s recordings and transmissions positioned at sites ranging from museums to the Golden Gate Bridge (installations that, beginning in 1976, he dubbed “sound sculptures”).

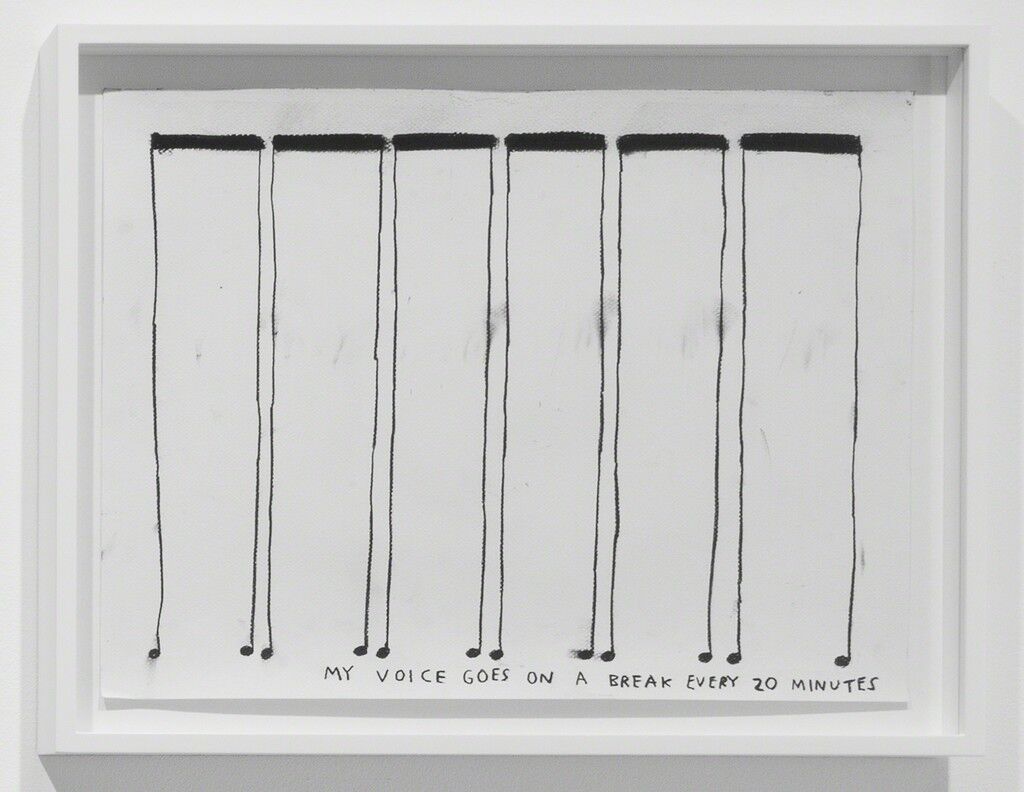

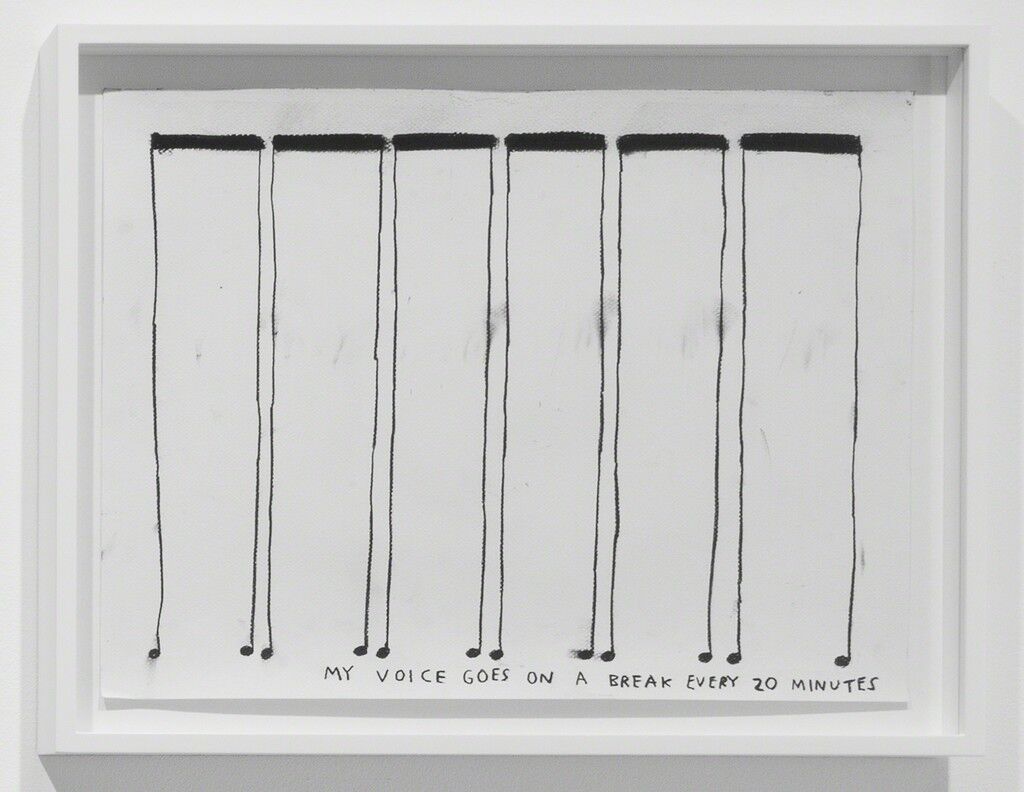

Christine Sun Kim

My Voice Goes on a Break Every 20 Minutes

Carroll / Fletcher

Sound’s life in a gallery context is constantly evolving. “Artists who want to exhibit sound in spaces designed for visual art must accede to the realities of such spaces,” said Kim-Cohen, who started experimenting with sound-as-art while playing in a series of Chicago grunge bands in the 1990s. He found that his conceptual approaches weren’t supported by the live-music contexts he was familiar with, and so he started approaching galleries to play his work.

While “sound art” became a recognized genre of artistic production around the early 1980s, if not earlier, it’s taken another 30 years for sonic artists to receive institutional recognition. In 2010, Scottish artist Susan Philipsz became the first Turner Prize winner in the history of the award to have created nothing visible or tangible. Instead, her prizewinning work was comprised of the sound of her voice singing three slightly different versions of a Scottish lament, installed under three bridges crossing the river Clyde in her hometown of Glasgow.

It wasn’t until 2013 that New York’s Museum of Modern Art held its first major exhibition of sonic art, “Soundings: A Contemporary Score.” The curator of the show, Barbara London explained that the institution’s greater attention to multimedia art was in part due “simply [to] improvements in media systems that let the museum display sonic work in less disruptive ways,” reported the New York Times.

This seminal sound show included works by the likes of Philipsz, Haroon Mirza, and Christine Sun Kim, and revealed how many contemporary sound artists are creating a new sonic palette—often using new and old electronics alike to compound how sound comes to shape not only a given physical space, but our media-saturated environment as a whole.

Susan Philipsz, War Damaged Musical Instruments (Shellac), 2015. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. © The artist and Konrad Fischer Galerie.

Haroon Mirza

Lo-Tech Reproposed, 2014

Lisson Gallery

Consider the work of U.K.-based Mirza, which buzzes and pulses with the amplified sounds of interference between transistor radios or electricity as it passes through LED lights. One of Mirza’s clear goals is to push us toward an understanding of how experiences can be shaped by the sounds around us. One of his best known works, Taka Tak (2008)—composed of an Indian chest, flashing lights, a turntable, and a spinning wooden sculpture rigged to create an industrial-sounding backing track—addresses popular music’s contested place in Muslim culture, and how it seeps nevertheless into daily life.

In this way, sound can still operate in an extremely visual way, especially when the apparatuses to produce it are visible (and sometimes fetishized). The use of specific media, like records and cassettes, or media players, like old radios, are “cultural signifiers,” according to Ryan Packard, composer, sound artist, and marketing director of Chicago’s Experimental Sound Studio, an artist-run organization that focuses on the recording, archiving, and presentation of sound. (They maintain the archives of Malachi Ritscher and Sun Ra as well as his work with the Arkestra.) The specificity of the sound equipment that’s used merges the aural with the visual by attaching the piece to a person, place, or time. “The sheer fact that it’s dated makes it a representation of time itself,” he said.

Packard also noted that sounds, and the manner in which they’re presented, have nuances similar to other artistic materials. “The timbre of records or tapes versus a digital recording,” he says, “that’s an aesthetic consideration just like choosing to use blue or red paint would be.”

Installation of Christine Sun Kim's Game of Skill at Galeria Zero. Courtesy of the artist.

For some artists, working with the medium means an even greater attention to small details, as well as to the underlying process by which sounds are generated and perceived. New York-based Sun Kim, who has been deaf from birth, looks closely at how we use sound and learn it visually and physically as much as aurally. “I live in a hearing person’s world. I understand sound according to others’ physical reactions to sounds,” Kim said. “I know what’s a polite sound, what’s an inappropriate sound.” But the artist wanted to “unlearn” these noises and recode them according to her own terms.

This prompted her to create Game of Skill 2.0 (2015), in which audiences listened to a reading of a text about the future written by Kim and voiced by a museum intern. The recording is only audible when a special sound-emitting device has its antenna touched to an overhead magnetic strip that cuts through the gallery space. Performed backward or forward, with the speed of the sound proportional to the participant’s movement, the piece physically enacts the process of “scrubbing,” by which one fast-forwards or rewinds through a recording.

The majority of Kim’s work—and, indeed, that of many sonic artists—is relegated to indoor spaces, where sound can be much more easily controlled. For Canadian artists Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller, however, who often create subtle sound installations outdoors, manipulating sound often comes down to dealing with mother nature. For their 2012 Documenta installation, Forest (for a thousand years), they placed 18 shoebox-sized speakers among the trees and stashed 4 subwoofers amidst the woodland underbrush of Kassel’s Karlsaue Park. These disguised devices played 28 minutes of sound collage that included everything from birdsong to artillery fire, whispers to explosions, collected by the artists from all over the world.

The piece depended on the use of a technology known as Ambisonics, developed in the 1970s, which creates a three-dimensional sound field and creates the sensation of sounds that “move” around the visitor. “We had to have speakers of exceptional quality to create the illusion of spatial movement,” Cardiff says, explaining that the subtleties of the shifts in sound could easily be lost to the surrounding ambient noise of the great outdoors.

The technology behind Cardiff and Miller’s work is often paramount to its success. To that end, they are “constantly migrating equipment” and updating their tools. But for curators, the decision to swap out audio equipment isn’t an easy one. “We basically do a traditional condition report before and after an installation of a media work,” said Gebbers, who explains she must make judgement calls about whether the specific device is more important than the sound it helps emit. “If not, then should we adapt the technology? Or is the specific sound created by the recording technology and the playing devices an integral component? It becomes fraught very fast.”

And Gebbers stresses that conserving and collecting sound art is another task that is very different to painting or object-based art works. “There is a huge and growing range of recording mediums and media player devices that need specific maintenance, expert knowledge, and spare parts,” she said.

This is mostly delegated to technical service companies which have to be payed for the installation and maintenance during the exhibition plus the rental of the devices. Perhaps the future holds specialized courses of conservation study, training a new generation who can revive a vintage Walkman or rebuild an MP3 the same way someone might fix faded pigment on a Rembrandt.

I have some huge boxes ready to be tuned into a cardboard fort/clubhouse that will be big enough for one person to sit inside while they listen. I plan to pain the outside up like wooden boards, and have little window cutouts. I have combined all the queens garden footage together and exported the soundtrack to use in my final piece now.

Water Effects: Bottomless and Animated

From the desk of Dave Garbe on Thursday, June 06, 2013 http://www.wargamingtradecraft.com/2013/06/water-effects-bottomless-and-animated.html

|

The next few posts of my Tin Can Tree project are some I've been wanting to tackle for a while - water! Over 3 posts, I'm going to show you how to create bottomless and animated water, (today) clear water and waterfalls. Worth noting is that these techniques could also be used to create other liquids like ooze and blood.

There's been a bit of a delay on getting back on these terrain posts, mostly due to some charity work, bronchitis and an interview, but here we are!

As a starting point, we'll look at opaque water - that means water you can't see through, or bottomless. It's great for adding water effects to tall structures like this tree, where it would be impractical to fill it with water effects. You an also use this method on a thin base to simulate deep water or make it appear like something is submerged and disappearing into the depths!

When you're doing a lot of pouring glue and paper mache like this, buy bulk. It's crazy cheap.

I'm starting out using white glue to level and raise the water level since there's a lip at the spout of the tree. Pour it in and use a rough brush to spread it around. This is going to take a while to dry, so don't expect to work on this for a while. (Quite possibly the rest of the day, depending how thick you pour it)

Now, technically, if you didn't have any water effect stuff that I'll cover later, you could make your water just out of white glue. There's a few ways:

One way would be to mix some paint in with the white glue. I'd recommend a dark blue because as you can see below with the black paint, white glue mixes in like white paint and lightens everything. You also don't have to fully mix. Once again, look at the black paint and white glue mix below and see how natural it looks with all the swirls. It also takes a lot of paint for a large area like this - unless you're doing bases, buy a larger container of hobby paint.

The other way is to wait for the glue to dry and paint it. While this would work, it's probably the ugliest option unless you're really good at painting 2-dimensional surfaces. You'd actually have to paint on waves and ripples if you want the water to look realistic instead of just blue.

Now I take heavy gel like from my Fire Effects tutorial and spread it all over. Give the gel some movement and consider it's container. For the round trunk, I applied the gel to look swirling.

After the gel has dried enough to paint on, I gave a light wash of blue, but being the first layer decided to go darker. Instead, I painted a thick wash of blue on and wiped most of it off with a cloth. (You can see the white undried gel showing through in the bottom-right photo.

After this, just repeat it over and over. When you get near the surface of the water, start using less paint and apply it thinner. This way, the top layers will be more transparent.

After a bunch of layers, we get something looking like this.

Not only have I used lighter blues, but also threw in some turquoise and other similar colours for variety.

Gel layered this thick can take weeks to fully dry.

Until then, there's still white from the gel in these photos. For time reasons, I waited until the top of the gel was dry, painted, gel'd again.

Once dry, the uneven bubbly varnish helped create a churning water look.

Here's the final image of the water in the tree trunk

There's been a bit of a delay on getting back on these terrain posts, mostly due to some charity work, bronchitis and an interview, but here we are!

As a starting point, we'll look at opaque water - that means water you can't see through, or bottomless. It's great for adding water effects to tall structures like this tree, where it would be impractical to fill it with water effects. You an also use this method on a thin base to simulate deep water or make it appear like something is submerged and disappearing into the depths!

When you're doing a lot of pouring glue and paper mache like this, buy bulk. It's crazy cheap.

I'm starting out using white glue to level and raise the water level since there's a lip at the spout of the tree. Pour it in and use a rough brush to spread it around. This is going to take a while to dry, so don't expect to work on this for a while. (Quite possibly the rest of the day, depending how thick you pour it)

Now, technically, if you didn't have any water effect stuff that I'll cover later, you could make your water just out of white glue. There's a few ways:

One way would be to mix some paint in with the white glue. I'd recommend a dark blue because as you can see below with the black paint, white glue mixes in like white paint and lightens everything. You also don't have to fully mix. Once again, look at the black paint and white glue mix below and see how natural it looks with all the swirls. It also takes a lot of paint for a large area like this - unless you're doing bases, buy a larger container of hobby paint.

The other way is to wait for the glue to dry and paint it. While this would work, it's probably the ugliest option unless you're really good at painting 2-dimensional surfaces. You'd actually have to paint on waves and ripples if you want the water to look realistic instead of just blue.

Now I take heavy gel like from my Fire Effects tutorial and spread it all over. Give the gel some movement and consider it's container. For the round trunk, I applied the gel to look swirling.

After the gel has dried enough to paint on, I gave a light wash of blue, but being the first layer decided to go darker. Instead, I painted a thick wash of blue on and wiped most of it off with a cloth. (You can see the white undried gel showing through in the bottom-right photo.

After this, just repeat it over and over. When you get near the surface of the water, start using less paint and apply it thinner. This way, the top layers will be more transparent.

After a bunch of layers, we get something looking like this.

Not only have I used lighter blues, but also threw in some turquoise and other similar colours for variety.

Gel layered this thick can take weeks to fully dry.

Until then, there's still white from the gel in these photos. For time reasons, I waited until the top of the gel was dry, painted, gel'd again.

As a final touch, I applied gloss varnish to the whole thing - BUT used it liberally and splotchy to create lots of little bubbles.

Once dry, the uneven bubbly varnish helped create a churning water look.

Here's the final image of the water in the tree trunk

Nostalgia - https://www.dictionary.com/browse/nostalgia

A wistful desire to return in thought or in fact to a former time in one's life, to one's home or homeland, or to one's family and friends; a sentimental yearning for the happiness of a former place or time.

Music-Evoked Nostalgia

https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/mental-mishaps/201105/music-evoked-nostalgia

Why do certain songs send us back?

Posted May 06, 2011

I found myself falling through my memories backwards in time after hearing a song from my high school days. A single song made me feel like I was 18 again while reminding me that I'm substantially older. For me, music can induce nostalgia quickly and easily.

Other sensory experiences can induce nostalgia as well. Proust, in the most famous literary example, was sent falling into nostalgia by the taste of a cookie dipped in tea (a petite madeleine, if you are looking to try the famous memory cookie). For others, it may be a smell or a sight that evokes a long-forgotten memory.

But music seems to be a powerful memory cue for many people. Schulkind, Hennis, and Rubin (1999) documented the power of songs to bring to mind previous events and times. They played popular songs from a variety of eras for both college students and older adults. They found that songs frequently evoked memories. Sometimes, as in my case, a song would evoke a general recollection - a memory for a life period such as high school, or college, or dating that certain someone from long ago. Other times, songs brought to mind specific recollections of particular events.

Schulkind and his colleagues found that the more emotion a song generated for someone, the more likely the song would cue a memory. In addition, older songs more often evoked memories for the older participants whereas recent tunes brought memories to mind more often for the college students.

What I found really interesting is that songs often evoked memories that were general rather than specific - the feeling of high school rather than a specific event; your time with someone rather than a single date. In a word, the songs evoked nostalgia. Of course not every song brought memories to mind. Actually only a minority of songs (but a large minority) evoked memories in Schulkind, Hennis, and Rubin's study. More recently Janata, Tomic, and Rakowski (2007) also reported that songs frequently evoked memories and they reported that one of the most common emotional responses named, even by college students, was nostalgia.

So the question is why do some songs evoke memories and feelings of nostalgia while others do not?

I suspect Proust and his cookie-evoked memory may hold the key. Proust noted that he had seen madeleine cookies many times since his childhood - apparently these are a common sight in French bakeries and pastry shops. But Proust had not tasted a madeleine dipped in tea since he was a small child. To evoke memories, sensations need precise connections. Proust stated that he had not eaten the cookies, particularly not dipped in tea, since his aunt had shared madeleines with him years earlier. Thus the sensation matched the original and crucially had not been diluted by other experiences since. The taste of the tea-dipped cookie brought to mind memories of his aunt, their time together, and that entire epoch in his life. A set of events were waiting in memory, waiting for the perfect cue or reminder - a cookie.

For me, and maybe for you, a song worked the same miracle of memory. I heard a song I had not heard in years. The song evoked a sense of nostalgia for my lost adolescence. For me the song was 30 years old, but for my students an N*Sync song from the late 90s can bring feelings of middle school nostalgia (apparently some of my students have fond memories of middle school).

The risk and the joy of listening to oldies is that memories may surface. A cookie, a song, a sight, a smell, almost any sensation can lead to memories and nostalgia. The effect may prove most profound when there are few encounters with the sensation between that long ago period and the present.

The Rehabilitation of an Old Emotion: A New Science of Nostalgia

https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/mind-guest-blog/the-rehabilitation-of-an-old-emotion-a-new-science-of-nostalgia/

By Clay Routledge on July 10, 2013

A Swiss physician named Johannes Hofer coined the term nostalgia in the late 17th century to describe what he considered to be a cerebral disease unique to Swiss mercenaries fighting wars far from home. Fast forward over three hundred years to the present day and nostalgia is everywhere. Old movie franchises are resurrected and rebooted, songs and albums that represent "the classics" for any given generation are remastered and rereleased, and old video games are given a high definition facelift and resold. Communities and civic organizations all over the nation host retro-themed recreational events (e.g., classic car shows, blast from the past dances), and many social media websites thrive, in part, because people long to return to their past by catching up with old friends. These are just a few examples of the human love affair with days gone by. But why is the past so seductive? And how do we reconcile the historical view of nostalgia as an illness with the fact that this desire to mentally time travel to the past is so ubiquitous? Is the nostalgia disease now pervasive, causing all sorts of physical and mental health problems? Or was Hofer (and many scholars and practitioners since) wrong to conceptualize nostalgia as an illness? For nearly the last decade my colleagues and I have been striving to answer these and other unanswered questions about nostalgia. We were specifically interested in resolving the questions of what characterizes the experience of nostalgia, what effects (positive or negative) it has on people, and what causes people to become nostalgic. We have now conducted dozens of laboratory experiments and surveys and can, with some confidence, offer a new perspective on this old emotion. What characterizes the experience of nostalgia? Look in the dictionary and you will find a rather general definition of nostalgia as "a sentimental longing or yearning for the past" But what does it mean to be nostalgic? My colleagues and I explored this question by asking participants to write at length about an experience of nostalgia. Trained coders then analyzed these nostalgic narratives. Results from these coded narratives indicated that nostalgic memories tend to be focused on momentous or personally meaningful life events that prominently features close others (e.g., friends, family, romantic partners). Family vacations, road trips with friends, weddings, graduations, birthday parties, and holiday gatherings with loved ones are examples of the kinds of cherished experiences that people revisit when engaging in nostalgia. In addition, when coded for emotion-related words, results indicated that positive emotion-related words were used far more frequently than negative emotion-related words. Nostalgic memories are happy memories. What effect does nostalgia have on people? It is hard to imagine nostalgia as a disease when considering its content. Hofer proposed that nostalgia caused symptoms such as anxiety, insomnia, irregular heartbeat, and disordered eating. And Hofer was not alone is his view that nostalgia was an ailment that led to a number of problematic symptoms. Indeed, until the later part of the 20th century nostalgia was viewed either as a medical disease of a mental illness. However, past work on nostalgia was largely non-scientific. That is, no controlled studies were conducted to determine the effects of nostalgia. My colleagues and I thought it was time for nostalgia to be properly placed under the empirical microscope and thus began conducting laboratory experiments in which we systematically contrasted the experience of nostalgia with other modes of thought to determine its true consequences. Once we started conducting experimental studies, nostalgia started to look like an emotion redeemed. In a nutshell, we found that nostalgia does not have any negative effects on people, but does generate a number of psychological benefits. To illustrate, here is a quick rundown of a typical nostalgia experiment. Participants arrive at the laboratory and are informed that they are going to complete a survey regarding attitudes and emotions. They then complete a number of questionnaires as part of the study. Critically, some participants are randomly assigned to the nostalgia condition and some are randomly assigned to a control condition. Those in the nostalgia condition are provided with the dictionary definition of nostalgia, asked to spend a few minutes thinking about an experience of nostalgia, and instructed to briefly write about this experience. Those in the control condition are asked to think and write about a different (non-nostalgic) experience. The specific experience used in the control condition varies from study to study. In some studies, for example, control participants are asked to write about an ordinary experience from the last week. In addition, different studies have employed entirely different methods for inducing nostalgia. For example, in some studies, music has been used to heighten nostalgia. After the nostalgia or control condition, all participants complete a range of questionnaires to assess the effects of nostalgia. These questionnaires typically assess states related to psychological health and well-being. Here is what these studies have found. Nostalgia, compared to control conditions, does not increase negative emotions, but it does increase positive emotions. As I mentioned before, nostalgic experiences tend to be characterized as positive and this feature of nostalgia appears to translate into actual mood. When nostalgia is induced in the lab, it puts people in a good mood. In other words, thinking about cherished experiences from the past makes people feel good in the present. Nostalgia, compared to control conditions, increases self-esteem as well as perceptions of meaning in life. By allowing people to revisit cherished life experiences, nostalgia boosts positive self-regard and promotes the feeling that life is full of meaning and purpose. Nostalgia, compared to control conditions, increases perceptions of social connectedness. Again, as previously mentioned, nostalgic experiences tend to be highly social in nature. The consequence of this is that nostalgia makes people feel closer to others. Nostalgia reminds people that they are loved and valued by close others. These are just a few examples of the psychological benefits of nostalgia that have been unearthed in recent studies. Other recent studies further indicate that nostalgia reduces stress and makes people feel energized, inspired, and optimistic about the future. The punch line of all this work is that nostalgia is good for people. Contrary to past assertions, nostalgia does not harm people; it benefits psychological health and well-being. So what causes people to become nostalgic? Hofer thought that nostalgia was caused by continuous vibrations of animal spirits through fibers in the middle brain. Others proposed that nostalgia resulted from damage to the eardrum and brain caused by the nonstop clanging of cowbells in the Alps. Though we found these explanations rather imaginative, not surprisingly, my colleagues and I thought a fresh look at the causes of nostalgia was in order. As a starting point, we asked participants to indicate what situations or experiences tend to make them feel nostalgic. Social interactions (e.g., getting together with an old friend), sensory imputs (e.g., smells, music), and tangible objects (e.g., old photographs) commonly inspire nostalgic feelings. However, negative mood was the most commonly reported cause of nostalgia and, within this general category, loneliness was the most frequently listed discrete negative emotion. These findings suggest that nostalgia is triggered by feelings that could be described as psychological threat. But further work was needed. My colleagues and I again turned to experimental methods to further examine the causes of nostalgia. In particular, we believed that negative mood, loneliness, and feelings of meaningless would be potent triggers of nostalgia. We reasoned this because of the psychological functions that nostalgia serves. That is, as previously discussed, nostalgia increases positive mood, perceptions of meaning, and a sense of connectedness to others. Thus, people may naturally turn to nostalgia if positive mood is threatened, a sense of meaning in life is undermined, or feelings of social connectedness are compromised. Experiments we conducted supported these proposals. In one study, participants were randomly assigned to read one of three news articles that were chosen to induce positive mood, negative mood, or no emotion. All participants then completed a questionnaire that assessed how nostalgic they felt at that moment. Participants who read the negative mood inducing article reported feeling more nostalgic than participants who read either the positive or neutral mood inducing articles. In another study, some participants were assigned to a condition that made them feel lonely. Specifically, they completed a personality questionnaire and were then provided with false feedback suggesting that they were high on a validated measure of loneliness. Participants in the control condition were given feedback suggesting they were not high on loneliness. Again, all participants then completed a measure of nostalgia. Participants in the loneliness condition reported being significantly more nostalgic than participants in the control condition. In yet another study, some participants read a philosophical essay regarding the cosmic insignificance of human life (a threat to perceived meaning) while other participants read a philosophical essay that had no direct connection to perceptions of meaning. Again, nostalgia was then measured. Participants in the meaning threat condition reported feeling significantly more nostalgic than participants in the control condition. In short, situations that trigger negative emotions, feelings of loneliness, and perceptions of meaninglessness cause people to become nostalgic. The Past has a Bright Future Above, I described just a few examples of the many studies recently conducted in the field of social psychology on the content, function, and triggers of nostalgia. Though it has taken a few hundred years, thanks to a revived interest in this old emotion and a more scientific approach to studying it, nostalgia is getting a conceptual makeover. Nostalgia is not a disease or mental illness. Instead, it is a psychological resource that people employ to counter negative emotions and feelings of vulnerability. Nostalgia allows people to use experiences from the past to help cope with challenges in the present. And current research is further probing the many ways that nostalgia promotes psychological health. It appears that nostalgia has a bright future.

Some concept ideas for site installation for my piece. At this stage I have definitely decided on nostalgia as my theme but still unsure on the specifics of what I am going to do. I will admit that I am struggling this time around with sculpture purely because the film side of things has thrown me off. I do wish I had chose a simpler topic to portray.

These videos were my first attempt at capturing locations that make me think of my childhood however a frustrating breeze drowned out most of the sea noises so I didnt really get the effect I was looking for.

How Do You Exhibit Sound Art?

Margaret Carrigan

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-exhibit-sound-art

Haroon Mirza

A Chamber for Horwitz; Sonakinatography Transcriptions in Surround Sound, 2015

Lisson Gallery

Sound art

has always been a tricky proposition, for obvious reasons: Unlike a painting or a sculpture, it doesn’t stay put. This unpredictable medium has provided a wealth of potentials for artists—and challenges for curators—whether it’s being exhibited in the white cube or in the wilds of a German forest.

“The presentation of a sound piece isn’t just about the installation of whatever media player you have on hand, plus some headphones,” said Anna-Catharina Gebbers, a curator at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin. Instead, it involves what she terms “the acoustic creation of space.”

When encountering an object-based work, the viewer has much more control over the experience. You can walk up to a painting to see its finer details; every so often, you’re even allowed to touch a sculpture to appreciate its full materiality. If you don’t like what you see, you can just close your eyes—but there’s no way to naturally close your ears.

That means addressing one of sound art’s chief hurdles. Sound essentially “leaks,” according to Gebbers. “As a curator, one of the first things I think about is how can I protect the sound piece from other sounds, like those generated by audio works in its proximity, or even just ambient noise.” She explains that our brains are constantly processing audio data, prompting numerous additional considerations in order to present a sound work in a way that adequately expresses the artist’s idea while making it accessible to the visitor.

Haroon Mirza, A Chamber for Horowitz; Sonakinatography Transcriptions in Surround Sound, 2015.

According to sound artist and historian Seth Kim-Cohen, this onus falls to artists as well as curators. “When you want to picnic in the park, you have to bring your own plates, napkins, and cutlery. You don’t expect a waiter to emerge offering place settings,” he said. “Likewise, the sound artist can’t blame the curator when he’s told that he can’t play his piece on massive speakers at 110 decibels in their storefront gallery.”

In its nascency, sound art generally was aligned with developments in avant-garde music, and so work was often presented in spaces designed with acoustics in mind. Kim-Cohen points out in his book In the Blink of an Ear: Towards a Non-Cochlear Sonic Sound (2009), that sound art has always forced a re-negotiation of the established relationships between artists and their materials, traditions, and audiences, especially after World War II. In 1948, American composer and artist John Cage composed his first silent composition. The 1952 work 4’33”—which featured roughly four and a half minutes of a pianist sitting on stage in silence while the audience listened to the shuffling and throat clearing of their neighbors—became one of the foundational moments in sonic art history.

Increasingly, as sound art became woven into the practices of Conceptual and Fluxus artists of the 1960s and ’70s like Joseph Beuys, Yoko Ono, and Alison Knowles, it also functioned as a form of institutional critique, the point being to transcend the physical space of the gallery or museum. Through the 1980s and ’90s, artists like Bill Fontana and Doug Aitken were harnessing the power of new forms of electronic media to not only record and document their work, but create immersive environments or events. Those include Aitken’s multi-panel video installations and Fontana’s recordings and transmissions positioned at sites ranging from museums to the Golden Gate Bridge (installations that, beginning in 1976, he dubbed “sound sculptures”).

Christine Sun Kim

My Voice Goes on a Break Every 20 Minutes

Carroll / Fletcher

Sound’s life in a gallery context is constantly evolving. “Artists who want to exhibit sound in spaces designed for visual art must accede to the realities of such spaces,” said Kim-Cohen, who started experimenting with sound-as-art while playing in a series of Chicago grunge bands in the 1990s. He found that his conceptual approaches weren’t supported by the live-music contexts he was familiar with, and so he started approaching galleries to play his work.

While “sound art” became a recognized genre of artistic production around the early 1980s, if not earlier, it’s taken another 30 years for sonic artists to receive institutional recognition. In 2010, Scottish artist Susan Philipsz became the first Turner Prize winner in the history of the award to have created nothing visible or tangible. Instead, her prizewinning work was comprised of the sound of her voice singing three slightly different versions of a Scottish lament, installed under three bridges crossing the river Clyde in her hometown of Glasgow.

It wasn’t until 2013 that New York’s Museum of Modern Art held its first major exhibition of sonic art, “Soundings: A Contemporary Score.” The curator of the show, Barbara London explained that the institution’s greater attention to multimedia art was in part due “simply [to] improvements in media systems that let the museum display sonic work in less disruptive ways,” reported the New York Times.

This seminal sound show included works by the likes of Philipsz, Haroon Mirza, and Christine Sun Kim, and revealed how many contemporary sound artists are creating a new sonic palette—often using new and old electronics alike to compound how sound comes to shape not only a given physical space, but our media-saturated environment as a whole.

Susan Philipsz, War Damaged Musical Instruments (Shellac), 2015. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. © The artist and Konrad Fischer Galerie.

Haroon Mirza

Lo-Tech Reproposed, 2014

Lisson Gallery

Consider the work of U.K.-based Mirza, which buzzes and pulses with the amplified sounds of interference between transistor radios or electricity as it passes through LED lights. One of Mirza’s clear goals is to push us toward an understanding of how experiences can be shaped by the sounds around us. One of his best known works, Taka Tak (2008)—composed of an Indian chest, flashing lights, a turntable, and a spinning wooden sculpture rigged to create an industrial-sounding backing track—addresses popular music’s contested place in Muslim culture, and how it seeps nevertheless into daily life.

In this way, sound can still operate in an extremely visual way, especially when the apparatuses to produce it are visible (and sometimes fetishized). The use of specific media, like records and cassettes, or media players, like old radios, are “cultural signifiers,” according to Ryan Packard, composer, sound artist, and marketing director of Chicago’s Experimental Sound Studio, an artist-run organization that focuses on the recording, archiving, and presentation of sound. (They maintain the archives of Malachi Ritscher and Sun Ra as well as his work with the Arkestra.) The specificity of the sound equipment that’s used merges the aural with the visual by attaching the piece to a person, place, or time. “The sheer fact that it’s dated makes it a representation of time itself,” he said.

Packard also noted that sounds, and the manner in which they’re presented, have nuances similar to other artistic materials. “The timbre of records or tapes versus a digital recording,” he says, “that’s an aesthetic consideration just like choosing to use blue or red paint would be.”

Installation of Christine Sun Kim's Game of Skill at Galeria Zero. Courtesy of the artist.

For some artists, working with the medium means an even greater attention to small details, as well as to the underlying process by which sounds are generated and perceived. New York-based Sun Kim, who has been deaf from birth, looks closely at how we use sound and learn it visually and physically as much as aurally. “I live in a hearing person’s world. I understand sound according to others’ physical reactions to sounds,” Kim said. “I know what’s a polite sound, what’s an inappropriate sound.” But the artist wanted to “unlearn” these noises and recode them according to her own terms.

This prompted her to create Game of Skill 2.0 (2015), in which audiences listened to a reading of a text about the future written by Kim and voiced by a museum intern. The recording is only audible when a special sound-emitting device has its antenna touched to an overhead magnetic strip that cuts through the gallery space. Performed backward or forward, with the speed of the sound proportional to the participant’s movement, the piece physically enacts the process of “scrubbing,” by which one fast-forwards or rewinds through a recording.

The majority of Kim’s work—and, indeed, that of many sonic artists—is relegated to indoor spaces, where sound can be much more easily controlled. For Canadian artists Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller, however, who often create subtle sound installations outdoors, manipulating sound often comes down to dealing with mother nature. For their 2012 Documenta installation, Forest (for a thousand years), they placed 18 shoebox-sized speakers among the trees and stashed 4 subwoofers amidst the woodland underbrush of Kassel’s Karlsaue Park. These disguised devices played 28 minutes of sound collage that included everything from birdsong to artillery fire, whispers to explosions, collected by the artists from all over the world.

The piece depended on the use of a technology known as Ambisonics, developed in the 1970s, which creates a three-dimensional sound field and creates the sensation of sounds that “move” around the visitor. “We had to have speakers of exceptional quality to create the illusion of spatial movement,” Cardiff says, explaining that the subtleties of the shifts in sound could easily be lost to the surrounding ambient noise of the great outdoors.

The technology behind Cardiff and Miller’s work is often paramount to its success. To that end, they are “constantly migrating equipment” and updating their tools. But for curators, the decision to swap out audio equipment isn’t an easy one. “We basically do a traditional condition report before and after an installation of a media work,” said Gebbers, who explains she must make judgement calls about whether the specific device is more important than the sound it helps emit. “If not, then should we adapt the technology? Or is the specific sound created by the recording technology and the playing devices an integral component? It becomes fraught very fast.”

And Gebbers stresses that conserving and collecting sound art is another task that is very different to painting or object-based art works. “There is a huge and growing range of recording mediums and media player devices that need specific maintenance, expert knowledge, and spare parts,” she said.

This is mostly delegated to technical service companies which have to be payed for the installation and maintenance during the exhibition plus the rental of the devices. Perhaps the future holds specialized courses of conservation study, training a new generation who can revive a vintage Walkman or rebuild an MP3 the same way someone might fix faded pigment on a Rembrandt.

Still trying to find ideas on how to create and exhibit my work, however I am now leaning towards

telling my personal memories that are triggered by specific sounds. I would set up a headset and portable music player in a quiet area, blocked away from the world so that my listener can immerse themselves.

I have some huge boxes ready to be tuned into a cardboard fort/clubhouse that will be big enough for one person to sit inside while they listen. I plan to pain the outside up like wooden boards, and have little window cutouts. I have combined all the queens garden footage together and exported the soundtrack to use in my final piece now.

After sitting down and recording my thoughts stream of consciousness style, Ive decided I quite like the way it sounds, each grandparent has around 5mins of story that I have told before editing. The tone of the piece is quite sad, because 3 out of 4 grandparents have passed away, but I still think my reminiscing classes as nostalgia.

After editing out the pauses, Im left with around 18mins of audio story-telling. Ive decided that the tone of the stories dont match a clubhouse style site, and so I have gone through old photos to find ones that match up with parts of my stories. Using premiere I have applied fading techniques to each photo so they slowly come in and out of the blackness at various points, giving my listener some visual references.

Ultimately, this did not turn out the way I originally planned back at the proposal level but I think it was a nice way for me to record some of my memories before they fade away. Still unknown whether I will let my family hear it though lol.

Animation 2/11

Submission day today, its funny how it doesnt seem like you have much to do until that final day lol. Overall Im ok with what I submitted, although there is plenty that I would like to go back and change as well. Consistancy of the characters being the main thing. However Im still considering it a step up from last semester, and I can only get better over the next couple of years with the screen production course. I felt a little bit dumb when I was doing the final render and noticed a couple of my frames didnt have any colour. I have no idea how that happened, my guess is sleep deprivation, but thanks to Ruby she quickly ninjaed some colour onto it for me so I could hand it in.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

BSA702 14/7

arrays and lists Quick and Easy Galaxy painting great tutorial I found when I was looking for a background for my pitch tomorrow. I want t...

-

Character/Game idea colour dropper - player has a set amount of time to pick a colour to stand on, all other colours drop out causing player...

-

2019.1.8f1 unity version - update home install to match. Look into the software bundles I got from humble and see if they are useable for cl...

-

Preliminary game-flow chart Make a title Colour Party Who is the game for Ages 6 and up What is the game play style 3D, Round based colour m...